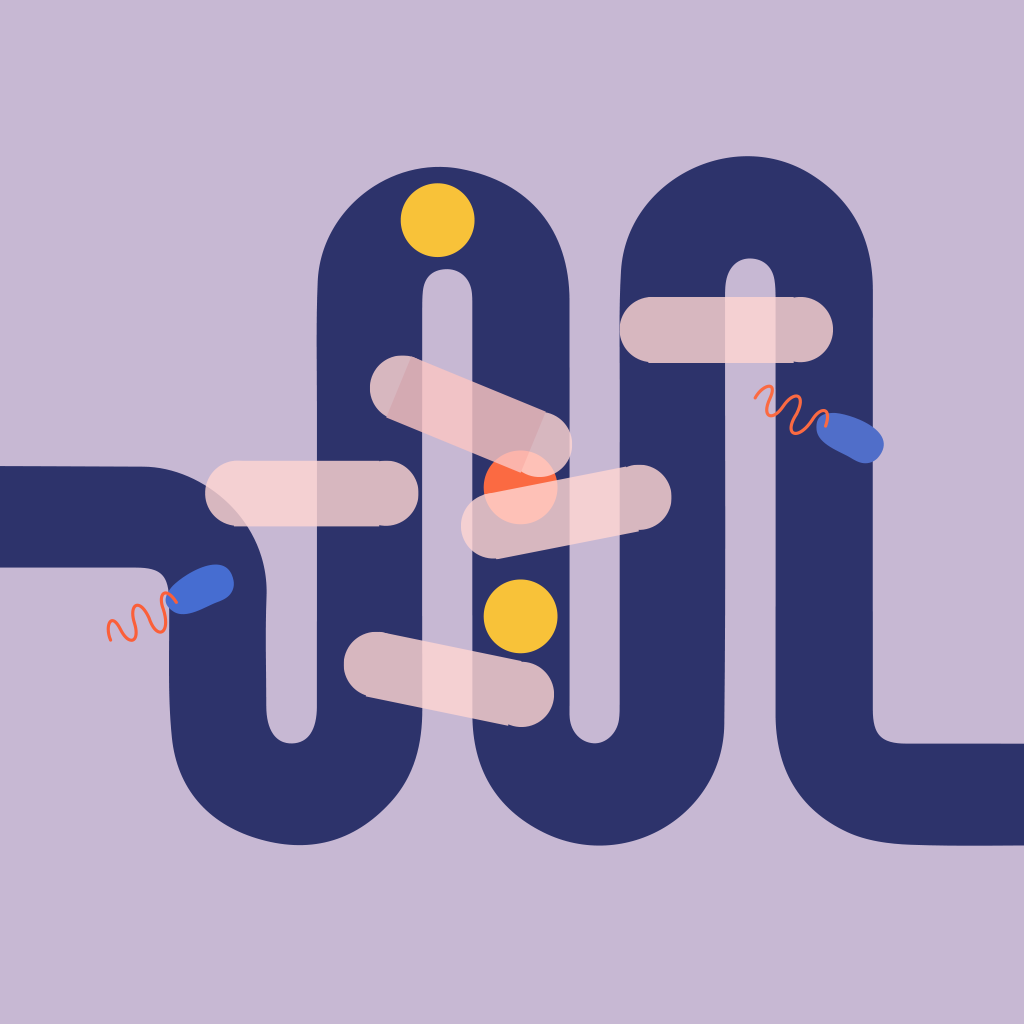

Human Gut

With roughly 50,000 to 500,000 microbial cells per teaspoon in our upper intestines and 500 billion cells per teaspoon in our colon, our gastrointestinal tract features microbes fighting for space on the mucus-lined interior of our body. Bathed in semi-digested foods from the outside world, some microbes make a living digesting protein-rich food, while other species are critical to help us digest the fiber in vegetarian meals. These microbial species are critical to our digestion and produce many vitamins in our diet, as well as many of our fouler smelling farts. The gut environment can contain hundreds of different species of microbes.

The Players

Ruminococcus species live in our intestines (gut) and help us digest food. We are unable to break down--or cut apart--the insoluble fiber molecules in plant material. Thanks to Ruminococcus species, we don’t have to. These ovoid shaped cells snip apart the plant material so that we can absorb the sugars through the lining of our gut. Other mammals rely on Ruminococcus to help them digest food as well. We share these microbial partners with cows, horses, and goats.

Akkermansia species are ovoid cells that may play a disproportionate role in human health, though like gut microbiome science, we are still in the early days of understanding what all the species are doing. Akkermansia are species that directly interact with the gut wall. They create molecules that act as signals to our body and feed off the sugars we produce in our gut mucus. Recent research by scientists has found that higher amounts of these species in human guts is seen in people with lower levels of general inflammation and lower obesity. It’s proposed that Akkermansia help make this possible by stabilized our gut barrier — keeping a healthy boundary between what passes through our gut and our own body. However, not all is good news. Other studies using mice have found that Akkermansia have also been associated with colon cancer by making red meat more dangerous to our gut. The science is still out on if and when these species are our foe or friend.

Bacteroides species, like other species in our gut are competing for food, space, and resources. The competition and predator prey dynamics that play out on a Savannah among wildebeests, antelope, lions, jaguars, cheetahs and giraffes exist at the microscopic level in our gut. Bacteroides species are abundant members of our complex gut ecosystem and these rod-shaped bacteria are using diverse strategies to protect their resources from competing bacteria. One strategy used by Bacteroides species, and other bacteria, is to produce biocins--highly specific antibiotics that kill off very specific bacteria. Current research is investigating if biocins produced by Bacteroides and other species of gut microbes can be used to kill those gut microbes like Clostridium difficile that cause diarrhea and other gut infections.

Bdellovibrio species are rare inhabitants of the human gut microbiome, but worthy of mention because of their unique lifestyle. Bdellovibrio bacteria whirl through their liquid environment like cheetahs hunting on savannahs. The bacteria attack their prey bacteria, burrowing inside of them. Bdellovibrio are bactiovors, feeding on the insides of their prey bacteria, then multiplying until they burst forth from the now dead host. As Bdellovibrio are bacteria that can hunt and feed on some of the bacteria that cause human and animal illnesses, they are being investigated as an alternative to antibiotics. Who knows, in the future we might be using microbes to directly kill off our microbe infections.